Scott Lincicome, Clark Packard, and Alfredo Carrillo Obregon

We have previously discussed how the Trump administration’s tariffs impose high costs on Americans, not only by raising taxes and prices but also by creating a complex maze of overlapping import regulations that compound costs and encourage abuse. A new lawsuit challenging US steel tariffs provides the latest example of this ever-growing problem, and it reveals a growing trade bureaucracy that’s effectively making up new—and quite possibly illegal—import barriers on the fly.

In a legal challenge to the administration’s assessment of Section 232 “national security” tariffs on steel, Illinois-based company Express Fasteners claims that US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) unlawfully charged higher duties on the company’s imports of machine screws and fasteners—so-called “derivative” products subject to the exceedingly complex rules governing steel-related imports. Published CBP guidance establishes that Section 232 duties apply “only on the value of the [derivative product’s] steel content.” Express Fasteners followed this guidance, reporting the imported products’ “steel content”—that is, the value of the steel used by the foreign manufacturer to make the derivative products—and their non-steel content, which includes the costs of manufacturing the derivative products. The company then paid corresponding duty rates: 50 percent for steel content and 20 percent (i.e., the “reciprocal” tariff applicable to imports from Taiwan) for everything else.

To the company’s surprise, CBP applied a 50 percent steel tariff on the full value of the imported products, translating to significant additional funds that Express Fasteners owed the government. The basis for CBP’s move? An unpublished December 2025 memorandum that narrows what qualifies as “non-steel content” by disallowing the inclusion of costs associated with turning steel into derivative products and that provides for a derivative product’s taxable “steel content” to be calculated as the value of the imported product minus its non-steel content. This secret change effectively required importers to pay “steel tariffs” on things that were clearly not steel, such as fabrication, machining, labor, and coating costs, thus substantially inflating the total tariff amount that an importer would have to pay the government.

The company says it learned of the memo only after being charged by CBP for the additional tariff amounts and then filing a protest. To top it all off, Express Fasteners only learned of CBP’s unpublished rule from another importer, not from the agency itself.

Express Fasteners’ experience is sadly not unique: CBP has reportedly enforced the Section 232 steel and aluminum tariffs more aggressively since issuing the memorandum. A corporate lobbyist interviewed by Politico reasoned that CBP is exploiting the ambiguities in the Section 232 steel and aluminum presidential proclamations for an “easy way to collect more revenue”—and to funnel additional tariff protection to a US steel industry that, as this Cato paper documents, has long benefited from government restrictions on foreign competition and a cozy relationship with the Trump administration in particular.

If Express Fasteners’ lawsuit is successful, the company would likely save some money in the short term. But the broader, longer-term implications for the Section 232 steel/aluminum tariff regime are unclear. The company is challenging CBP’s failure to follow the Administrative Procedure Act’s notice-and-comment requirements, so a successful suit might only force CBP to reintroduce these provisions through the lawful rulemaking process. That transparency—and the message sent by judicial limits on agency lawlessness—would be good, but it probably won’t reduce importers’ tariff liability. Nevertheless, the case is notable because it illustrates several significant issues:

First, as complex as the US tariff system in 2026 may seem from a 30,000-foot view—Cato’s tariff complexity flowchart below should give you an idea—it’s even more impenetrable for the companies and, especially, the small businesses that must interpret or navigate the system daily. The ambiguity and obscurity of the system’s rules amplify these costs, especially when applied to complex imports or, as the Express Fasteners case shows, when interpreted in a surprisingly protectionist way by CBP. If a company’s interpretation of these rules doesn’t align with CBP’s version, that compnay can face unexpected—and inflated—tariff liabilities and maybe even penalties for noncompliance.

Second, the case underscores that the administration’s hard-line tariff stance extends beyond rates to aggressive and opaque enforcement. The more than 20 tariff legal regimes now in US law are only part of the story; how they are enforced—with limited notice and little transparency—can matter just as much. History (and public choice theory) teaches us that trade rules will most likely be interpreted to favor import-sensitive domestic companies with more political clout—at American consumers’ expense.

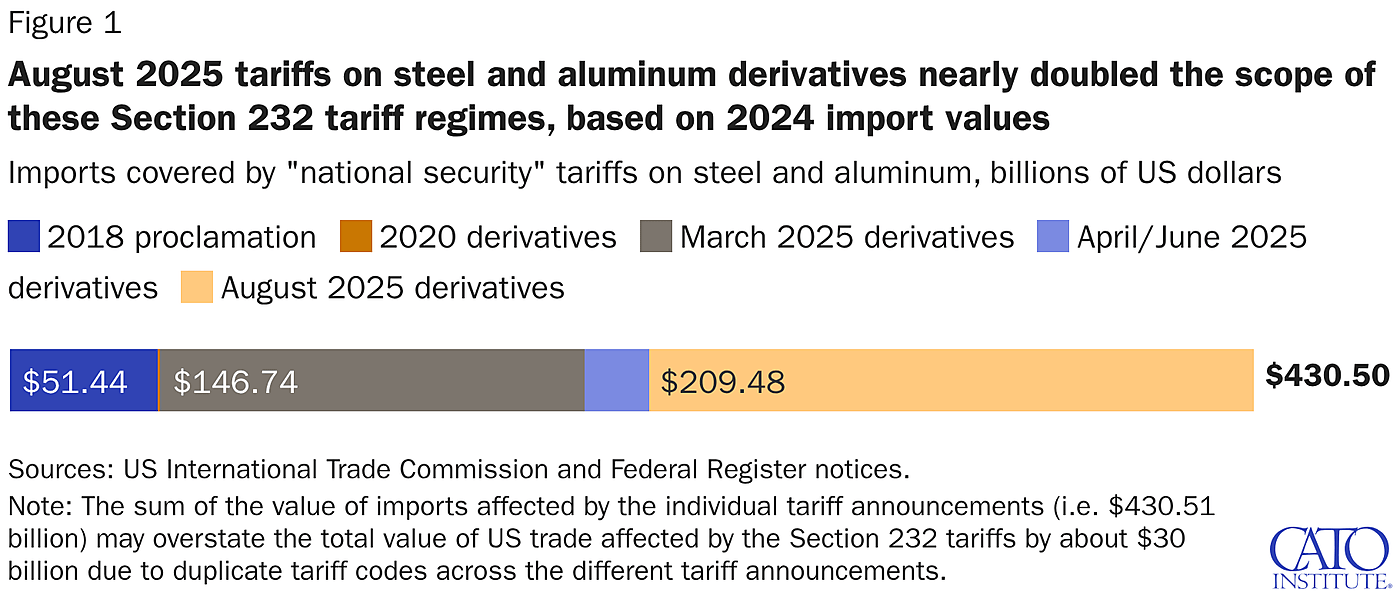

Third, the case shows that the Section 232 tariffs’ rules for “derivatives” and content are clearly being used as a backdoor means of assessing additional tariffs. We previously flagged that the “tariff inclusion” process instituted as part of the president’s tightening of the Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum almost doubled the coverage of this tariff regime, based on the import values of the covered Harmonized Tariff Schedule codes (Figure 1). Those tariffs were quietly published three days before taking effect. Now, it’s also clear that the administration will exploit regulatory gaps and ambiguities to further increase the tariffs’ magnitude, in the process eschewing the transparency and accountability that the legal rulemaking process provides. With several other Section 232 tariffs now in place or pending, the room for abuse is massive.

Finally, whatever CBP’s intent, the agency’s unpublished rule reinforces the perception (at the very least) that US trade policy was designed to do the steel industry’s bidding. As we documented, the federal government has coddled domestic steelmakers for more than 60 years, and the “revolving door” between Big Steel and the Trump administration spins quickly. The Express Fasteners case shows that government officials seem to keep finding new and inventive ways to penalize imports made with foreign steel, thus lining the pockets of their friends in the steel industry and penalizing millions of American consumers who don’t have an ally in the White House.

The administration may believe that helping the domestic industry achieve a 1 percent increase in its annual steel production justifies the high costs, complexity, and uncertainty induced by its protectionist trade policies. Companies like Express Fasteners and millions of Americans employed in steel-consuming industries would probably beg to differ.